Content warning: sexual assault

This is an essay about depictions of sexual violence in sculpture and the responsibilities of museums and galleries who display them. I visited the Borghese Gallery in Rome about a month ago, and when I saw the pieces of art that I write about here, I had a really visceral reaction to them that I’m still trying to turn into words. I had a conversation with someone last week about trying to write about things that are “hard and soft,” as she put it, and this is one of those things. When the political, personal, and aesthetic get this entangled, I get stressed but I also care a lot. So bear with me while I look at these objects again and think about what’s wrong with them and, especially, what’s wrong with the way they’ve been curated.

So first, the old art. Two of the most famous baroque marbles ever carved, both by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, are part of the Borghese’s permanent collection and were commissioned by Scipione Borghese, who built the gallery. One of these is Apollo and Daphne, finished in 1625, which depicts the mythical tale of the god Apollo’s charmed pursuit of Daphne, a naiad who has been cursed by Cupid to hate him.

Bernini captures in stone the moment in which Apollo reaches out to grab Daphne, at the same moment in which her father, a river god, turns her into a tree to save her from Apollo’s clutches. Her fingers are sprouting leaves, her smooth flesh turning to rough bark, her toes rooting down into the earth as Apollo’s arms wrap around her. It is an exquisite feat of sculpture, so filled with movement and dynamism while being, of course, frozen in marble. It is also a tale, however misted in fantasy and divine powers, of stalking and attempted sexual assault.

In the next room at the Borghese is another of Bernini’s renderings of the ancient gods and goddesses. This one is The Rape of Proserpina, completed in 1622 when Bernini was only 23. It is an even more violent story than Apollo and Daphne’s. In this case, Pluto, the god of the underworld, kidnaps Proserpina, daughter of the goddess of the harvest, called Ceres or Demeter, and forces her to marry him (In Greek, their names are Persephone and Hades).

Bernini does not shy away from the violence of the moment in which Pluto snatches Proserpina. Stone tears trickle down Proserpina’s face as she screams out, and the indents of Pluto’s fingers gripping her flesh are delicately rendered in stone. Again, it’s full of movement - Proserpina has leapt into the air in her struggle to get away, and Pluto’s body ripples with muscles, all flexing in his effort to contain her. Also again, it’s a remarkable feat of sculpture - the bodies are full of life, the composition is perfectly balanced, and the complexity of the narrative is packed into this single, emotive moment.

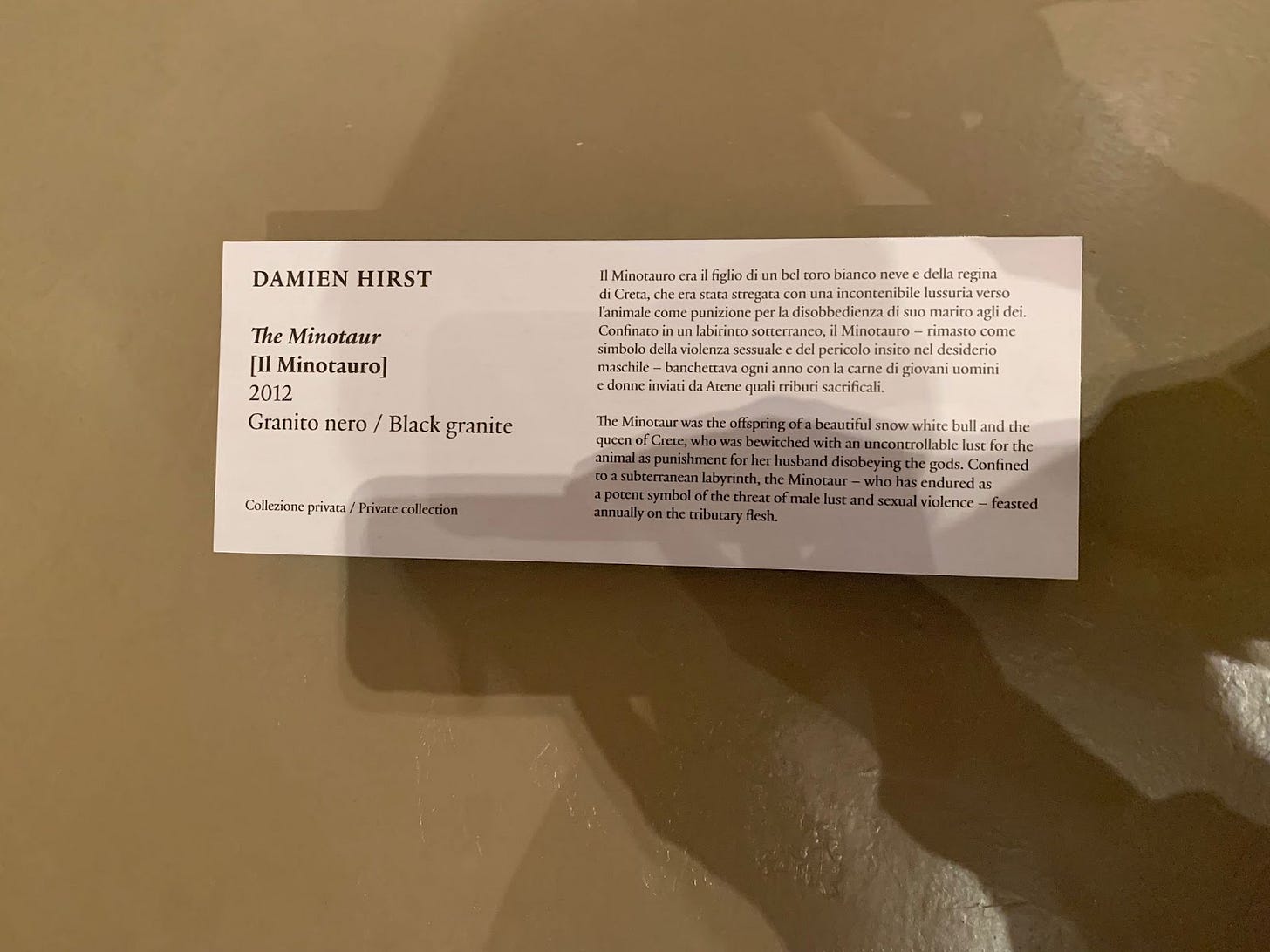

Currently, there is a third sculptural depiction of rape on view at the Borghese. It is Damien Hirst’s The Minotaur (2012), on view as part of a re-installation of his series “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,” originally shown at the Venice Biennale in 2017. When I Googled this piece of art, the top hit was “Here Are the Absolute Worst Artworks We Saw Around the World in 2017.” And yet! It is on display in one of the most prominent museums in Rome, if not Italy, if not Europe! This sculpture also references a Greek/Roman mythical story. It is a graphic depiction of the penetrative rape of a nameless human woman by the Minotaur, a creature with the head of a bull and the body of a man. In the legend of the Minotaur, the monster was the son of the Queen of Crete and a bull, and was given seven men and seven maidens every so often upon which to feast. He was kept at the center of a labyrinth, and eventually slayed by Theseus, with the help of Ariadne’s famous ball of string.

According to the wall text next to Hirst’s work, this is a depiction of the annual feasting “on the tributary flesh” - wording that, while theoretically referencing the myth of the Minotaur, equates rape with “feasting” and refers to the female figure simply as “flesh.” The humanity of this person is invisible, erased. She serves only to gratify the Minotaur’s lust, and the voyeuristic lust of the artist and subsequently the viewer. The object is overtly pornographic, not just because of its subject matter, but also because it shares the maligned tropes of contemporary pornography - gratuitously violent sex and the depiction of nonconsensual sex as sexy.

Bernini’s sculptures are are not, I do not think, pornographic. In fact, I’m struck by the romance with which we might say Bernini treats his subjects. The women’s expressions are full of fear, but the men look like they’re having fun. Like they’re enjoying the “thrill of the chase.” Like, in a rom com from the 90s, the next scene could be a happy couple walking through autumnal Central Park, laughing about how they hated each other when they first met. Which is problematic, obviously!

I was deeply disturbed by The Minotaur, in a way that I was not by Apollo and Daphne or The Rape of Proserpina, and I am still thinking about exactly why. All three depict terrible scenes of sexual violence. The two Berninis do not depict rape itself, but moments leading up to it. Therefore the viewer can avoid grappling with the direct visual gut punch of assault. Does that make them better, morally and/or artistically? You can make the opposite argument that Hirst’s graphic depiction is better, because it confronts the viewer with the reality of sexual assault, while Bernini’s allows us to hide behind a veneer of fantasy and romance. How much does their aesthetic quality matter? I think the Berninis are more beautiful, and more skillfully made objects than the Hirst. They have a dignity to them that comes partly from the quality of the craftsmanship and their compositional and aesthetic balance. That sense of dignity makes them feel more respectful to the subjects they portray. But this is a soft part of this soft-hard subject - my emotional response to the aesthetic of these works is only mine, and I know that it comes partly from my bias towards “classic” works of art and also my already deeply-held hatred of Damien Hirst. And I’m uncomfortable owning the fact that I like the Berninis at all, because I also think they’re very flawed.

I could spend a lot of time weighing up which of these works is “better” or “worse” than the others, but I could never get past my own opinion, because that’s all I have. As a viewer of art, I have the opportunity to think about and form responses to the objects I look at. But museums and galleries and the people in charge of them have the RESPONSIBILITY to engage with the objects they steward or curate and help the rest of us to understand what they can illuminate about the experience of being human, which is what art does. The Borghese, in this instance, failed. The juxtaposition of these different sculptural depictions of rape hit me as soon as I entered the gallery, but I don’t think that was the curators’ intention. Nothing about the curation of the galleries or the texts accompanying these objects engaged with ways of representing assault in the seventeenth versus the twenty-first century. Nothing warned the viewer that they were about to encounter three images of sexual violence. In fact, there was no curatorial engagement with them at all, really, beyond text identifying them and explaining the basic plot of the myths they reference.

And so I have to ask, why install a purposefully anachronistic show that is directly in conversation with ancient sculpture and texts NEXT TO ancient sculpture and Renaissance and Baroque sculpture that is ALSO in conversation with the antiquities and not do the hard and interesting work of talking about what the pieces are saying to each other, and how they help draw out new meanings through their juxtapositions? What is the point of this show if not to do that? I think installing contemporary art next to old art, or in old spaces, can be incredibly stimulating and creative. There is so much potential to put objects in new contexts and raise difficult and exciting questions about them. This is not it.

I’m left with so many questions about what an acceptable way to depict sexual assault in art is. Can someone whose life has not been touched by sexual assault still make art about it? Does it matter that the stories referenced by the three works in the Borghese are myths, not real stories? Where are the works by WOMEN about this???? How have cultural understandings of rape changed between 1622 and 2012? Can work that is problematic still be beautiful? If so, how do we handle that? These are hard and big questions that I’m still thinking about (except the women question - I know exactly what I think about that one). They are also really interesting questions. And I am so disappointed that the Borghese failed so fundamentally to attempt to answer them. In fact, I believe they have actively done harm in the way that they installed these works without context or reflection. Violence against women, it should go without saying, is an emergency. Rape and sexual violence between and against people of all genders is an emergency. Museums and galleries should know this, and act accordingly. There is no excuse for being part of the problem.

tl;dr: You can’t just put three statues of rape on view in a museum and not talk about their implications

Some Other Things I’m Thinking About

All Too Well (10-Minute Version)

The White Pube’s pamphlet ideas for a new art world, which has some very good ideas.

I really like Otegha Uwagba’s podcast “In Good Company,” in which she basically talks to women who are self-employed/freelancers very directly about how they make money and what their emotions around their financial decisions are. It feels surprisingly (and depressingly?) radical.

This 2020 essay in the LRB called “Is it OK to have a child?” by Meehan Crist, about the ethics of reproduction in a global emergency, which is currently in front of the LRB paywall for COP26.

“Why laziness is a radical act,” from Lola Olufemi in gal-dem in 2019.

The word viridescent, which a kid I tutor gave me as a synonym for “green” - impressive.

It is knitting season again and I’m working on feeling courageous enough to start a balaclava (so far in my career as a knitter I’ve only made hats and also once when I was 13 I boldly made leg warmers with a lot of help from my aunt). Tips welcome!!