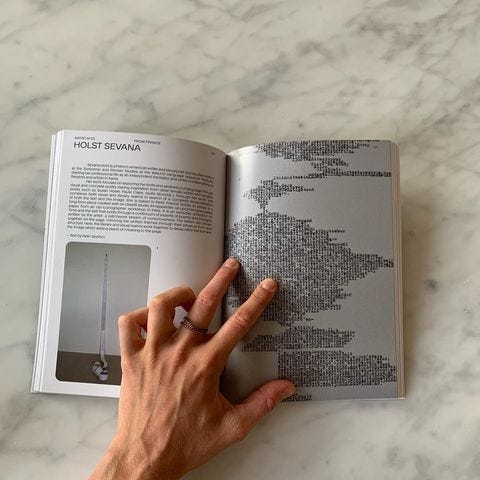

This week, I interviewed Sevana Holst, a visual poet based in Paris. She showed work at the ReA! art fair in Milan in September 2021 and was recently the winner of the "Look Forward" artist residency in Naples. Her poetry was published in the first volume of Deleuzine. Her work is a fascinating blend of poetry and visual art, and I have been dying to talk to her about it for ages. She’s so cool! You can see more of her work here.

Eliza: I’ve only seen your work online, which is sad, and I would love to see it in person, but to start I was hoping you could just tell me about what you do - your artistic ethos, however you want to put it.

Sevana: I would say that my work is a mix of visual poetry and concrete poetry. It’s a rabbit hole I fell down a couple years ago. Like everyone, you know, I’ve always kind of written a little bit, so I was trying to find a way to write. But I wanted to add an extra dimension to what I was doing. So layering an aesthetic value onto what you’re writing, asking, do the aesthetics of the word and how you do the mise en page, or how you put your words together, does that add meaning to what you are writing, or not? Kind of playing on that, and then pushing that even further with concrete poetry, playing with typography and just letters and words that are even more important than the text that you are trying to relay. So I would say that I do visual and concrete poetry. That game of playing with words is really fun to me.

E: Can you define concrete poetry?

S: Concrete poetry is the game of using the aesthetics of letters and typography to create poetry and to create works of art, and the aesthetics of that surpasses the importance of text in a regular format.

E: Do you think at all about the tension or difference between the identities of artist and writer? Do you think of yourself as both?

S: That’s a good question. I had always wanted to write, but I realised that where I am right now, I’m not a good enough writer. So how can I still write even though I know that if I’m just writing, it’s not what I want it to be? Playing with adding the visual realm to the literary realm and kind of associating the two together is what I’ve tried to do. Maybe this is just to reassure me, but I associate the visual realm and the literary realm together to desacralize both of them. I can still be honest in my work and try to do something that is good or complex or meaningful. I don’t have any pretensions to be a good writer or a very good visual artist.

E: It seems like you obviously are both, and I’m interested in how you occupy both of those identities, which I think sometimes we think about as being opposites almost, even though they obviously overlap a lot.

S: Yeah.

E: I also want to hear about your materials - you work with typewriters, and I want to know where those came from - how did you get interested in the things you work with?

S: I have always been drawn to arte povera, I think it's really beautiful. I only use typewriters to make my work, and that was really by chance. I ended up getting a typewriter and started playing with it, but now it’s really part of my work and I don't see myself doing it any differently. First of all, I am interested in exploring the limits and aesthetics of the words on the page, so if you have a typewriter you are physically limited in what you can put into the typewriter - how big can it be, what things can fit in there. I’ve tried things like paper, aluminum foil, a bunch of things. Playing with those limitations is interesting to me. Then there is a ritualistic part of it for me now - if I’m working, I’m using my typewriter and there is this ritual act of physically printing each letter onto the page that I really like and is really part of my process now.

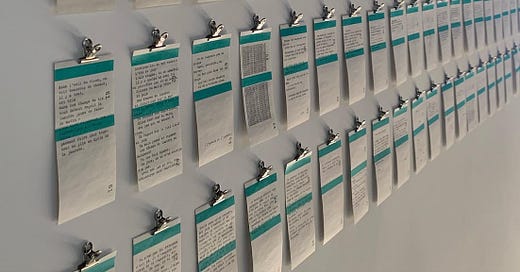

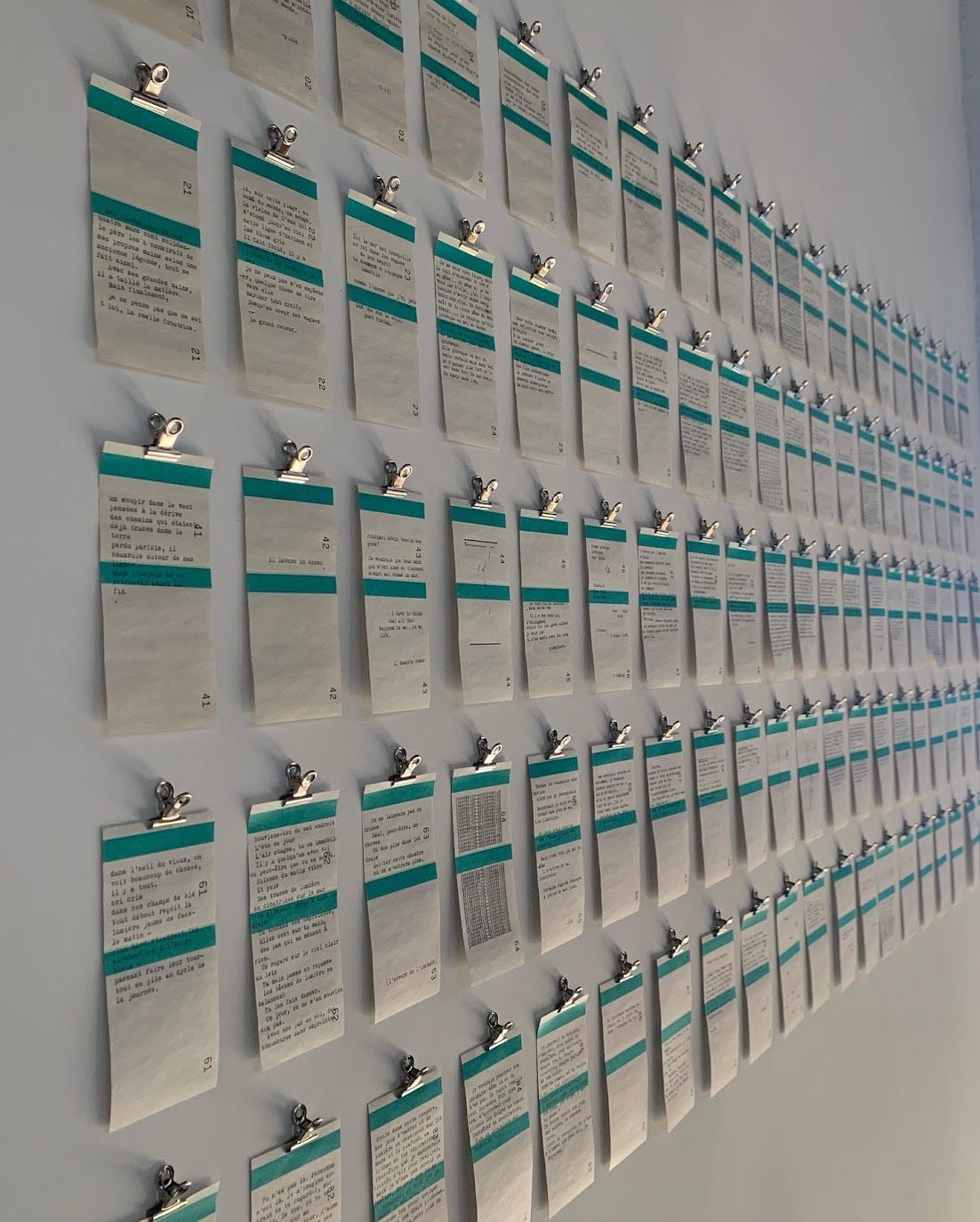

As far as materials go, most of what I use is upcycled or recycled paper. I was lucky enough to get stacks of really old, good paper from this iconographer in Paris - someone who makes icons in churches. He had a workshop and he passed away and I got all of this old paper. I’ve been using that for the past year. And then, I’ve done a series on cash register rolls, or order pads from restaurants. I like using poor materials - only poor materials for now. I’m interested in discovering different formats as well, but it’s kind of fun, again still in this idea of the game, thinking about how I can repurpose things. And like, does the support, does the material matter in the work that you’re trying to do?

E: Do you think it does? That feels like a big question. Do you think what you write changes in response to what you are writing on?

S: I think sometimes it can be a way to downplay what you’re writing or what your text is, and make it almost less pretentious. And there’s also just the aesthetic aspect of it. For example, I just did a whole series with order pads from a restaurant, and they’re all numbered one to a hundred, so it’s a series of a hundred mini poems, essentially. The order pad itself isn’t a beautiful piece of paper, but I thought that visually it was really interesting to have a hundred of them just numbered with a tiny bit of colour and then just the text on it. I guess it’s just what I find visually pleasing in the moment, you know?

E: I’ve noticed that some, maybe most, of your texts are multilingual, and I want to hear you talk about how you think about language when you’re writing, and mixing.

S: Well, as you know, growing up between the States and France, I’m bilingual, so it means that I’m comfortable in both languages. But the space in my mind is completely a mix of languages. So if I’m just writing for myself, I’m always writing in a mix of English and French, and that just kind of continued into my work. Some things are only in French, some things are only in English, but a lot of times I mix the two. It takes effort to literally understand all the text in my work - you really have to lean in just to be able to read it. So you can choose to just take the visual aspects, or you can just take the text. So for me, because I'm already mixing those elements, mixing two languages on top of that seems fine to me. The meaning is still there for me, and the texts that I write generally are quite intimate - it’s all just my personal thoughts, and they’re naturally mixed in two languages, so that’s just how they come out.

E: How do you imagine your viewer/reader interacting with your works? Do you want them to lean in and read every word, or do you want them to see it as a whole?

S: This is something that I hadn’t really thought about until my first exhibit. I saw people that I didn’t know looking at my pieces for the first time hanging up on a wall. So I got to see people interact with my work who didn’t know my work for the first time. Some people lean in and the text is really important - they lean in and look at it and really want to read the texts. And other people just kind of take whatever visual impression is given to them. And I like that you have the choice to do both. That is kind of the purpose of what I do: there are both aspects and one is not more important than the other.

E: When I’ve looked at your work, I’ve thought a lot about the tension between narrative in the writing and abstraction in the visual. I find it really interesting that you are making shapes or forms that are abstract but also the work is really narrative. You could say it’s figural but also abstract, and I think it’s fascinating how it is on both sides of that line.

S: I like playing around with those two. And even sometimes in the texts, I find it fun to start off with something that is quite narrative, but then little by little you kind of lose the reader. So most of the time, my texts end up more abstract in the end than in the beginning of the text, and you can notice that a lot depending on how you are looking at and consuming my work.

E: I’ve seen that you’ve been writing some poems that are just published digitally, and I’m wondering how that has felt for you?

S: I find it to be more difficult because I don’t have this extra layer to hide behind when I’m writing. So it’s something that I would like to do more of, but I find it really intimidating to just write. But it is still something that I like to do and would like to do more of.

E: I can see how it would feel more vulnerable

S: Completely, that’s the right word, I was going to say naked. You’re just there, there’s nothing else.

E: I also want to ask you about the logistics of your life as an artist / writer, because I’m always really curious about how people have made it work to make what they make. So what’s your life like?

S: This is still pretty new to me. I’ve just been doing this for a couple of years now, and I’ve done a few exhibits now and have started selling my work in the past year, and that’s always nice, but that’s not how I pay for my food. I’ve been a freelance translator for the past five years now. When I moved to Paris to start studying, I was working in a theatre, and then little by little I started doing little bits of translation work, and I’ve been able to pick that up more. It’s great because it’s words words words! And it’s flexible, so it allows me to actually focus on what I’m really interested in doing, which is this. And I stopped my studies to do this - last September, I was supposed to start my masters degree, and I was like, I wonder what could happen if I was able to just spend as much time as possible working on this thing. How can I be as honest as possible about the amount of time I can put into something and see how far I can develop it.

E: What are you working on right now?

S: I’m working on a little book right now that will hopefully be done soon, with this series that I was telling you about of 100 little poems. Hopefully once that’s done I'll be able to show the piece in a space and have the book go along with it. What I'm doing is quite niche, and I do work alone mostly, but it’s fun to work with other people, friends or creatives, who are doing something different. So for example I collaborated on a photography series with my really good friend Marie Estebanez. We were working on traces of light, and she was able to capture traces of light on walls, and she developed them. We had six photos and I took those and passed them into my typewriter. We had agreed on a poem together that I wrote onto the images. So collaborating on stuff like that is fun. And I collaborated with a good friend of mine, Christophe Brunnquell, who is an art director here in Paris, for this photography book he did for this photographer, Gregoire Alexandre, and they used some of my poems that they projected up onto the models that they were photographing. So that should come out soon hopefully, maybe next month.

E: That’s so fun, collaboration is always fun and interesting, to see things in different ways.

S: Yeah, I’m just in such a narrow tunnel of what I’m interested in so it’s always good to be with other people who are like, hey what about this, you have never thought about this but this could be cool too.

E: Definitely. Thanks so much for chatting, it was so nice to talk to you! I’ve loved seeing your work on Instagram for so long, and it’s been so nice to learn about it from you.

S: Thank you so much for this! Bisous!

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Some Other Things I’m Thinking About

Just when I thought the 21st century couldn’t get worse, it did. Hello Handmaid’s Tale!! Hello to my fellow makers of a “domestic supply of infants”!!

I’m so unbelievably disappointed in the Democratic party. “Characteristically, the Democrats never really believed that a political movement could and would actually deliver on its promises. They could not conceive that tactical evasions and temporary compromises were actually just that: tactical evasions and temporary compromises, not the basis for an entire political party’s continued existence.” Get your shit together guys!!!

I really agree with Rebecca Traister that continuing to say “rich women will be fine” is not helpful. First of all, they won’t always - yes, they will be able to end pregnancies if they want to, but they will still not be able to access emergency care for miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, or other complications if they live in states where providing that care is becoming illegal. Second, as Traister writes, “if these past years with COVID have taught us anything, it’s that if you tell middle-class white people that they will be fine, they will not give a rat’s ass about anyone else. And so this message, intended to engender empathy and provoke action and commitment, may instead have been an anesthetizing one. It may have permitted middle-class white people, with their significant political clout, to sleepwalk comfortably — as they have through all of Roe’s existence — into the waiting jaws of illegality.”

I’m reading Notes to Self, an essay collection by Irish writer Emilie Pine, and she writes about her struggles with infertility in Ireland pre-2018, when abortion was still illegal there. Her descriptions of the way she was denied any information about what was happening in her body when she had a miscarriage (the nurses literally said “we can’t tell you anything”), because it was illegal for medical professionals to privilege her as a patient over the foetus, are a grim reminder of how many people have recent experience of living under conditions like those coming (or already here) in the US.